This retro shooter renaissance took hold in 2018, led by Dusk, Amid Evil, and Project Warlock - among others. The developers behind each game interpreted 90s shooter design in their own unique ways, finding ways to reconfigure it for an audience that, in many cases, wasn’t even born in the 90s. Now, with all three developers working on their next projects, I figured it was a perfect time to catch up with them, reflecting on the making of their games, the zeitgeist they started, and where it’s all going to go from here.

Embracing the Ugly

The problem with defining a ‘90s shooter’ is that this was a decade of seismic technical progress that created several significant design styles; an era that began with the blue corridors of Wolfenstein 3D, progressed through Doom, Duke Nukem 3D and the Build games, the onset of 3D graphics with Quake, then concluded with technical tour-de-force Unreal and of course Half-life. With so many great blueprints to work from, it’s inevitable that everyone has their own ideas about what made this era special, with indie developers approaching it from many different angles. As Project Warlock creator Kuba Cislo puts it, “Everyone has to pick a timeline, and from that timeline pick the most important elements to them.” Dusk developer David Szymanski, for instance, was always about embracing the ugly. While the famously grotty Quake seems like an obvious reference point, his true low-poly love from the era was something far more obscure. “Playing a game called Chasm: The Rift was the first time I saw that look,” he says. “The game had its own really weird Doom Alpha sort of engine, but they also had this ability to render 3D models. I desperately wanted to make something with this blocky, chunky look to it, and I can’t really explain why that is!” Cislo’s stance on the 90s shooter aesthetic couldn’t be more different, with Project Warlock’s sprite-based art style and cramped corridors channeling Wolfenstein 3D. “Sprites are my favourite design choice ever,” he says. “They give you that cool feedback that models don’t - it just feels more crisp, and sometimes if the 3D models are not done correctly they just look janky.” Clearly, one developer’s jank is another one’s treasure. Cislo was just 18 when he made Project Warlock. So how did a game from 1992 become a design obsession for someone born in a different millennium? Cislo has fond memories of watching his father play Doom 3, Doom and Duke Nukem 3D, but it was a series of clandestine primary school sessions that introduced him to Nazi hunter B.J. Blazkowicz. “We had this room where we could stay after school, and there we had a couple of PCs with Commander Keen, DOSMario and Wolfenstein 3D,” he tells me. “Those childhood memories are important, and that’s what stuck with me.” (spare a thought for those of us who were only able to play Minesweeper and Spider Solitaire on our oppressively adminned school PCs.) Each game has a distinctive look - Dusk is crude and low-poly, Project Warlock is sprite-based and flat, while Amid Evil evokes the vibrant vistas of 80s sci-fi art more than any 90s game. Szymanski admits that there’s no modern magic to Dusk’s art style, and that beyond a deep-seated love for jankiness it was partly borne of a lack of documentation on making low-poly models in a modern game, and partly because he was “too dumb to know what those modern techniques might be.” With its fantasy theme, Amid Evil was dubbed as a spiritual successor to Hexen, but really its neon palettes, sprawling levels and psychedelic vistas bore little resemblance to its supposed ancestor. When I suggest to Amid Evil artist Simon Rance that his work looks more like the vintage sci-fi art of Steve Dodd, he admits that it was indeed an inspiration, and that the Heretic-Hexen comparisons were mostly for marketing reasons. In working on Amid Evil, Rance says his focus was more about capturing the feelings of mystery and wonder that games like that evoked, rather than trying to recreate the games themselves. “When making the art I was thinking about how playing those games felt,” he says. “It would be like your mind would fill in the blanks, especially when you were a kid.” Within games, Rance was most inspired by the strange planetscapes of Unreal, which was the first time he experienced a shooter that created the sense of exploring just a small segment of a vast alien world. These indie games refuted narrative, condensing it to intertitles between chapters or short blocks of text readable on plaques. Their mechanics were distilled, focused around the same few functions and controls we used when our hands made the intrepid journey from directional arrow controls to WASD in the 90s - just faster, more immediate, and with a few modern flourishes like the character progression in Warlock. All three games are structured around chapters and episodes, with each level separated by punchy end-of-mission screens first popularised by the original Doom - where every kill, item and secret we uncovered was punctuated by a machine-gun rattle and that rolling intermission music. The intermission screen carries powerful associations - with Doom, with victory, but also with the inevitable frustration of not having collected all the secrets. “It’s part of that 90s feeling, and it still feels really good to play,” says Rance. “Hunting the secrets to me was a big part of those games. It made you want to go back, master the levels and get them. We wanted to keep that feeling of exploration.” Other callbacks were more subtle. Amid Evil’s entire weapon progression closely followed that of Doom; its rocket launcher equivalent, the Celestial Claw, was assigned the number ‘5’, while Aeturnum, its screenwiping answer to the BFG9000, was at ‘7’. Reloading has no business in speed-strafing forward-charging games like these, so when in Dusk you press the ‘R’ key, instead of reloading you casually flip your gun in your hands. It’s a playful touch, stylishly giving a finger to the stern realism that became a hallmark of 2000s shooters.

End of an era?

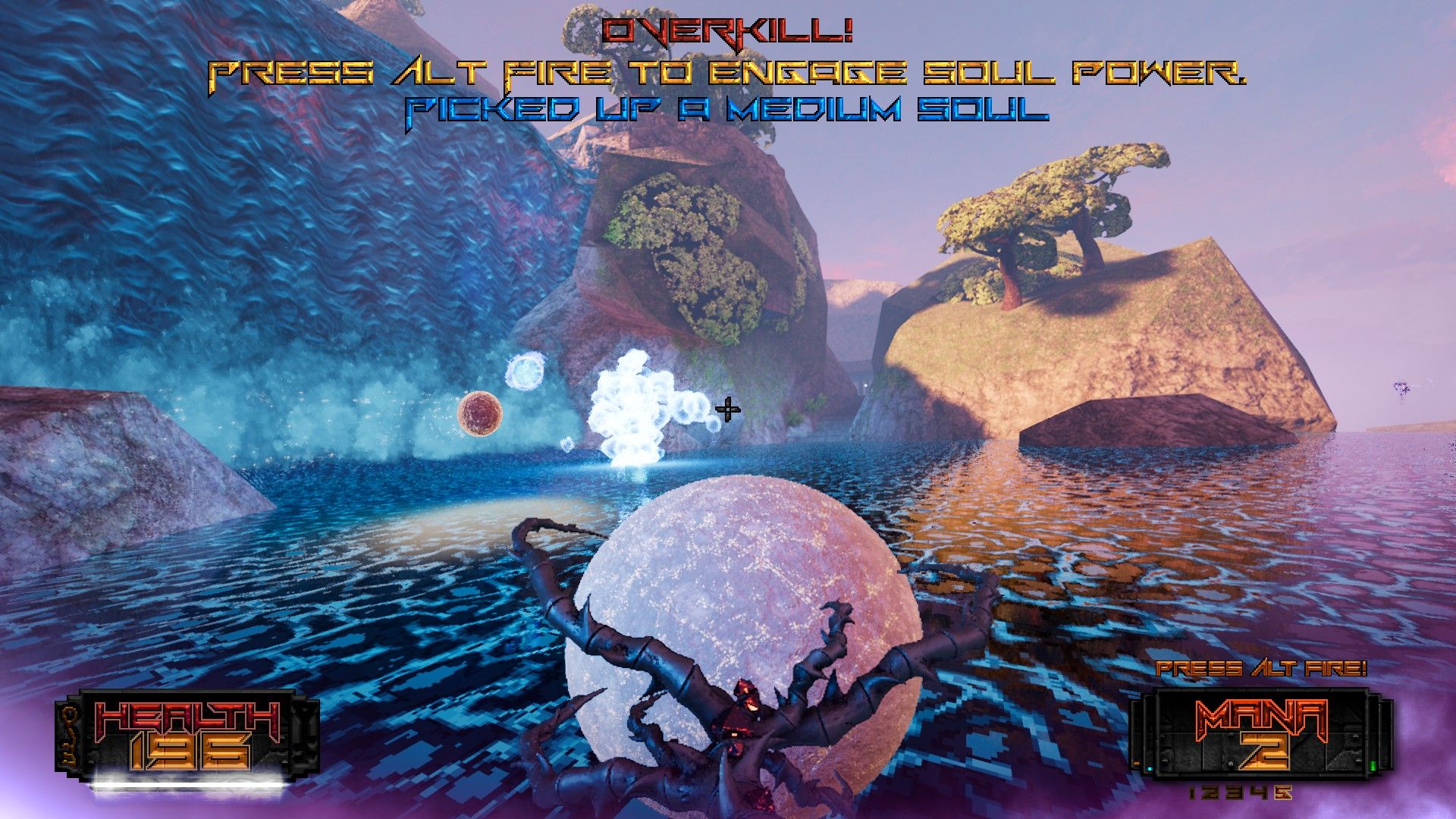

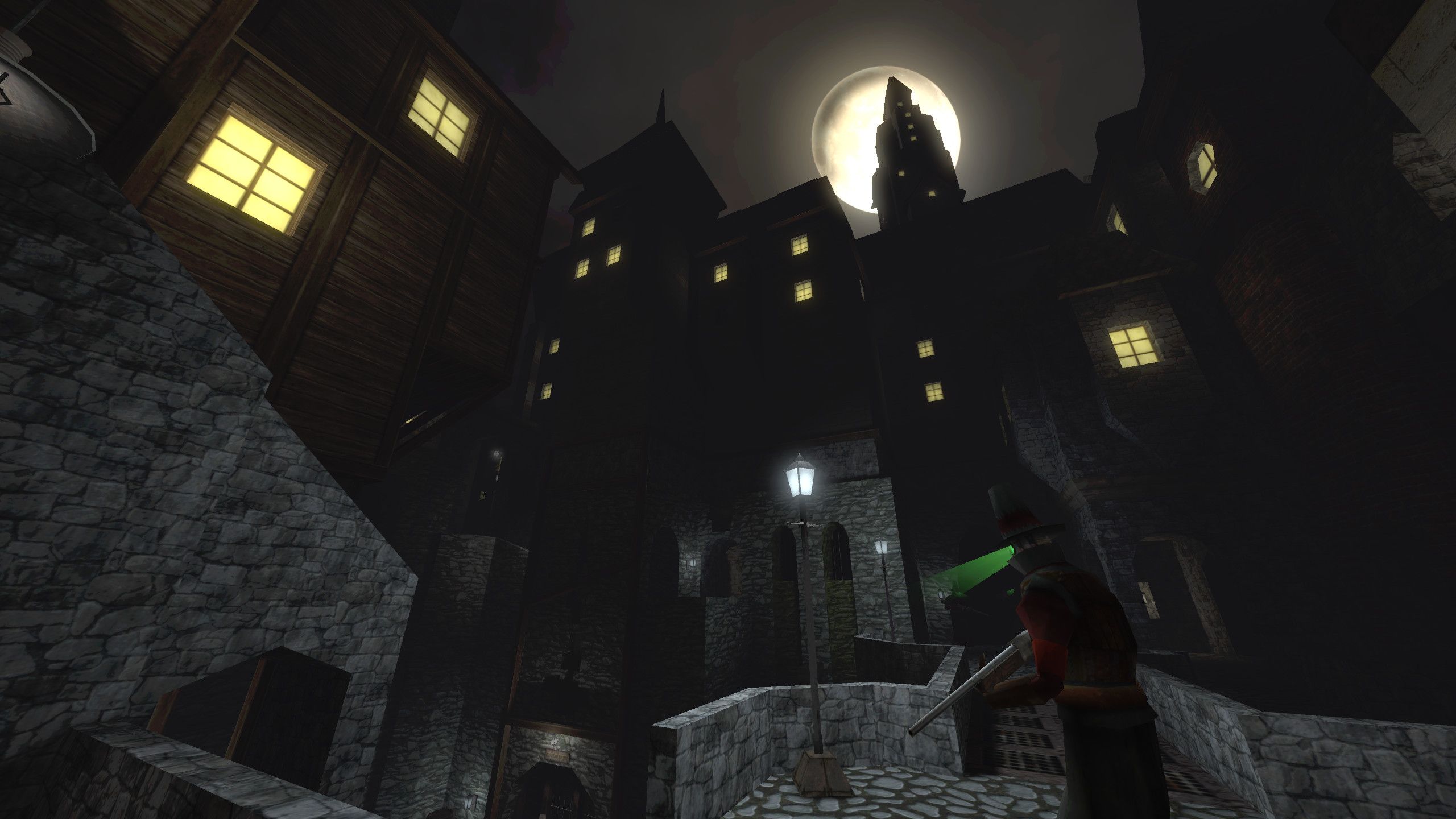

Each of these games was a success, and when they launched in 2018, they spearheaded the retro renaissance, with other developers soon boarding this bloodiest of bandwagons. But now, three years on, with their subsequent projects well underway, the three developers have all faced the question of how to meaningfully evolve within that retro framework. How much can you really improve upon something that’s, to an extent, archaic by design? Szymanski toyed with the question when Dusk first came out. “We talked about a Dusk sequel, and what that would even look like. Would it be a Half-life style game? Would we jump forward to a 2004-style FPS?” Even though he believes that Dusk’s fundamentals are strong enough for a sequel inspired by a different era, he’s more interested in exploring new genres rather than following what he describes as a retro-inspired FPS zeitgeist. “The retro boomer shooter is probably here to stay in some form”, he tells me. “But we’ve kind of peaked as far as saturation for boomer shooter throwbacks goes, I think.” So Szymanski moved on, and teamed up with Dillon Rogers to work on Gloomwood - a stealthy, Thief-inspired immersive sim-horror hybrid. While it retains the chunky aesthetic of Dusk, it’s a more brooding, slower-paced game, set in the shadowy streets of a Victorian steampunk city. Along with his publisher, New Blood Interactive founder Dave Oshry, Szymanski believes that the immersive sim could be the “next comparable indie zeitgeist” due for a retro revival. Amid Evil developer Indefatigable is currently working on an expansion for the game, as well as a VR version. The campaign will have a different pacing, taking the player on a heroic journey across that surreal fantasy land instead of jumping into distinct worlds from a Quake-like hub. “Where Amid Evil was an open-ended ‘defeat evil’ sort of thing, here you’re on a quest to get the Axe of the Black Labyrinth, so we’re having fun with that.” Beyond that, Rance agrees with Szymanski that it may be time to move on from the congested boomer shooter. “There’s more and more of these games coming out and they’re starting to blend together,” he says. “You can kind of tell it’s reaching the end, and doesn’t feel as new and exciting as it did two, three years ago.” He reveals to me that he and Leon Zawada at Indefatigable are working on a new game unrelated to Amid Evil or first-person shooters. It will continue to be informed by their love of retro games, but that’s all he can reveal for now. Which leaves us with Kuba Cislo, currently Knee-deep in the making of Project Warlock 2. One of the perks in modelling his first game on Wolfenstein 3D is that there’s a natural progression from there through the 90s, and he describes the sequel as having “more of a 1995 feeling”. There will be more verticality, and Buckshot Software is dropping hand-drawn monsters in favour of low-poly animated models which it converted into sprites. This creates an interesting 2.5/3D fusion aesthetic that still looks retro, but never actually existed in the 90s. “Each monster has around 10 death animations and is viewable from eight sides,” he says. “You can kill enemies by headshots, blow their limbs off, overkill them. This would not have been possible had everything been drawn by hand.” Even after all these years, Cislo is still unearthing arcane knowledge from the FPS classics, and recently made a discovery about hitscan in one of the great Build era shooters. “I found out recently that in Blood there’s a way to counter those hit-scanner cultists using the alternative attack of the Thompson machine gun,” he says. “I took this into account for Warlock 2. I like hitscanning because it gives you that added pressure, but I’m going to give players the tools to counter it this time.” When I float the idea to Cislo that the boomer shooter wave is past its peak, he says that his own journey with it is far from over. “I think that there is still something new and interesting to be discovered in the genre, and I will try to find it,” he concludes. Looking at the retro shooter landscape today, you can understand why some would think that the genre has become oversaturated. Upcoming games like WRATH: Aeon of Ruin, Effigy, Graven and Dread Templar all clearly pay tribute to the 90s golden era - and maybe they’ll turn out great - but are they tearing away at an itch that has already been scratched? The nostalgic allure will always be there for those who, like me, grew up on Doom and Duke, but the novelty isn’t what it was a few years ago. Maybe instead of blending into a homogeneous puree of rusted iron and brown mulch, the retro shooter wave should instead go into a chaotic postmodern overdrive. Ultrakill, for example, eschews retro aesthetics for bright base colours and Minecraft-adjacent voxel art, hordes of barely animated enemies and arcade-like score counters. Then there’s Cruelty Squad - a jarring but hypnotic shooter that looks like it’s set in the world you might emerge into after escaping a randomised Windows 95 Maze screensaver. These games vaguely nod to the past, like lurid fever dreams or psychedelic trips that warp old memories, but garble it to the point that they become something new. In their own weird ways, they’re moving forward. When I suggest to David Szymanski that Cruelty Squad represents a kind of DMT death-scream for the retro shooter wave, he laughs, and points out that the game could also lead the immersive sim wave that he’s predicting. “The thing with Cruelty Squad is that it’s actually an immersive sim,” he points out. “So maybe it’s kind of the dying breath of the retro shooter, and also the ugly birth or rebirth of the immersive sim.”

.jpg/BROK/resize/690%3E/format/jpg/quality/70/warlock%20(2).jpg)